Home

Contents

1. Speech: Supreme Court (2019)

2. Speech: Rethink 50th anniversary event (House of Parliament, 2022)

3. Keynote Speech: Derbyshire County Council Consultation (Chesterfield, 2024)

4. Keynote Speech at Comensus Conference (UCLan, 2024)

5. Speech: Service User Voice at HIEM/Mental Health Alliance Learning Event, (March 2024)

6. Joint Keynote Speech at HIEM/Mental Health Alliance Learning Event, Nottingham (March 2025)

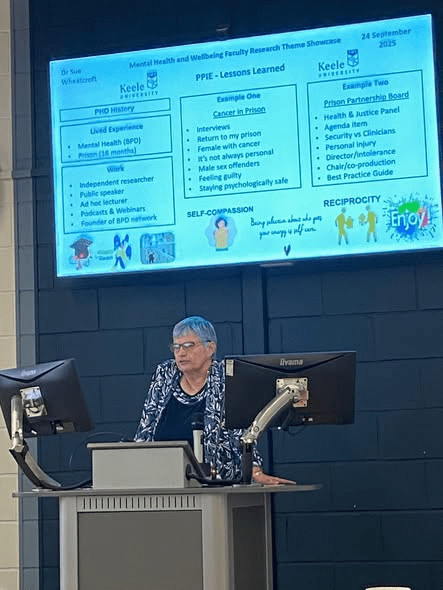

7. Speech at the Mental Health & Wellbeing Faculty research theme Showcase, Stafford (24 September 2025)

1. Speech: Supreme Court (2019)

Delivered at the Empowering Women, Transforming Lives conference at the Supreme Court, on 4 September 2019:

I was in segregation and had nothing. No clothes, no radio, no writing materials and nothing to read. What I did have was a razor blade. I wasn’t often strip-searched because I didn’t have a substance abuse problem, so I was able to smuggle it in. I didn’t intend using it; I had it ‘just in case’. But after several hours of staring at the wall and listening to the shouting and screaming coming from the other cells, I suddenly felt desperate. I cut my wrist. It wasn’t a suicide attempt. I didn’t want to die but doing something extreme made me feel better. I didn’t understand it but couldn’t seem to control it. The cuts were deep and there was a lot of blood. I let the blood drip onto the table and then used it to write on the walls.

Deputy manager Paul (not his real name), came in and told me to wash it off. I refused. He took hold of my head and pushed it onto the bloody table. ‘Now are you going to take it off?’ he said, nastily. ‘No!’ I replied. He pushed my head into the corner of the table until it was against the wall. There was blood in my hair and on my shirt. I wanted to stop him and get him off me. I picked up some congealed blood from the table and wiped it on the side of his shirt. He got hold of my arm and put it up my back. ‘One move and I will show you a whole new world of pain’, he said. I didn’t move. He told the officers to leave the cell and said he would be the last to leave. ‘I bet you would love to go for me now, wouldn’t you?’ he whispered, but that was the last thing on my mind. I didn’t say anything. He said, ‘thanks for the assault’, and left.

A nurse came to see me. The wound was quite deep, so she put a couple of steri-strips on, and then dressed it. The next morning, I was given my belongings. I had a shower and was grateful for the clean clothes.

Paul had put me on report for throwing congealed blood at him and so endangering his health or personal safety. My blood could have been contaminated, the adjudicator told me, and it had caused Paul considerable distress. I looked at Paul; he certainly didn’t look distressed. In fact, he seemed to be grinning at me. I pleaded not guilty because I had not thrown it at him; I had merely wiped it on his shirt in order to stop him hurting me. There was no malice intended and I didn’t feel I was being reckless with his health. I was found guilty, of course, and received more time in Segregation.

You may be thinking ‘why didn’t she just try and wash the word off and all that could have been avoided’. That’s what the officers said afterwards. I had caused myself all that grief because of my bad behaviour. I have Borderline Personality Disorder. Therefore, I am an attention-seeker. The only person who tried to understand was the prison psychologist, but she didn’t have time to treat me. Her job, she said, was to keep me out of segregation.

By the time of the incident with Paul, I had already been in segregation a number of times. Out of the 12 months I spent in this particular prison, a total of 3 months was in healthcare and 5 months in segregation. My way of coping in prison was to draw pictures and write stories on the walls of my cell. Some of them were funny, some were dark, and some were extreme. Everything I was feeling at the time was displayed on those walls. I understand now how ill I was, but at no time did anyone want to know what they meant or why I needed to do it. It invariably led me to segregation, but I never thought of the consequences. It was a compulsion, and the only way I could find to calm myself down.

In segregation, my behaviour became more extreme. As a punishment for the graffiti, I had all writing materials confiscated. Instead, I used coffee to write on the walls. The way the coffee made the letters drip down the wall made the cell look almost gothic. I felt safe, cocooned, there was hardly a space left on the walls. Eventually, I was taken to another cell and left there while my old cell was cleaned. I had no belongings at all, and the water was turned off in case I tried to flood the cell. All I had was the water in the toilet and a toilet roll. I wet the wall, made a word out of the toilet paper, and stuck it to the damp wall. I won’t tell you what the word was, I think you can guess.

Prison is an extreme environment and it brings out extreme behaviour in people. Ironically, two of the most compassionate officers I met were the two female officers in the cell at the same time as me and Paul. But they were afraid of him when he was in that mood. He could be very jolly when things were going well, but he had a dark side. His officers loved him, though, he always backed them, whatever they did.

I will never forget my time in segregation. Not because of my experience. I feel I gave as good as I got. But some of the women seemed to have given up. And this is why, when I came out, I started my volunteer work. I have set up my own support groups in Derbyshire for people with Borderline Personality Disorder. And I have done a considerable amount of work for the Revolving Doors Agency, including contributing to the Bradley Report review, 10 years on. One thing that that many ex-offenders have in common is the desire to help those still inside and through the gate. As part of the Health and Justice Lived Experience Panel, I have been back into the women’s estate to speak to the women about not giving up. I want them to know that their life means something and that they can still achieve their ambitions, because they are worth something. This was part of the pre-release skills project that we devised and piloted, and that is now embedded at the prison.

I would like to finish with one memory I have of my time in segregation that I am sure will stay with me forever. A woman a couple of cells away from me was due to go to court for sentencing and had been fretting about it for days. Not because of her case but because of her elderly grandmother, who was making the long trip to see her in court. But on the day, the officers never came to fetch the woman. She asked the senior officer, time and time again, what was happening, but he told her to shut up. I heard him laughing about it to his colleagues who, I think, he was trying to impress. I remember the woman sobbing, saying over and over, why are you doing this to me?’ It was heart-breaking. I never knew her name and I never saw her but she, and others like her, is the reason why I will never give up trying to bring change to the criminal justice system.

Thank you

2. Speech: Rethink 50th anniversary event (House of Parliament, 2022)

My speech

Thank you Mark and thank you for inviting me here today.

In 2015 I suffered a mental health crisis that led to a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder, or BPD. In the UK this is also known as emotionally unstable personality disorder, or EUPD. As the name suggests, it is a disorder of the emotions. When in crisis, we struggle to manage our thoughts and feelings and find it difficult to self-soothe or calm down. We need to do something extreme so that we can re-set our emotions and behavioural patterns. Some people self-harm, others commit an offence and some end their own life. 7 in 10 people with BPD self-harm and 1 in 10 end their own lives. 1 in 10! BPD is a severe mental illness.

In 2017 I was in recovery. It had been a rough couple of years during which time I had received no help at all for my mental health problems from statutory services. In fact, by trying, or should I say, begging for help and being refused, my mental health deteriorated, with disastrous consequences. I went to prison and my disabled partner was placed in a care home. On leaving prison, I found a private therapist, and my recovery began. I started thinking of others with BPD. Not everyone can afford to go private, and I couldn’t bear the thought of them going through what I had, so I decided to start a support group, and that’s when I first came into contact with RETHINK Mental Illness. Through their Derbyshire Peer and Recovery Support Service, I managed to set up the group and keep it going. We will celebrate our 5th anniversary in October. Over 250 people have passed through our service, from all over the UK and several from overseas. RETHINK Mental Illness have supported us since the beginning, and I can’t thank them enough.

I have also worked with RETHINK Mental Illness on their national lived experience advisory board and community’s advisory panel. Having such faith placed in me has spurred me on to do more and I am now a member of the East Midland Academic Health Science Network PPI Senate and the Revolving Doors Agency. I am also a fellow of the Fair Access to Justice Institute and am on the research team for the University of Central Lancashire’s Offender Personality Disorder Pathway Higher Education Programme. And this brings me to what I believe is imperative for the future of all mental health treatment: adequate education and training. People talk about trauma-informed care and of course, this is essential, but sometimes even that’s not enough. A real understanding of the condition you’re treating is vital.

The vast majority of people with BPD have suffered some kind of childhood trauma. This could be mental, emotional, physical or sexual abuse. Sometimes, it is all of these. When these children grow up, they often face stigma from statutory services, who see them as mere attention-seekers. But that’s because they don’t understand. The number of professionals, whether it be in health or criminal justice, who are openly hostile to those with BPD is incredible, and wrong.

Before my mental health crisis, I was an academic in history, and a published author. Now, I am a campaigner for mental health and women in prison. I want people at all levels, whether strategic or front line, to look beyond what they are seeing and to understand why people behave the way they do. What has happened to them?

I was 55 years of age when I was diagnosed. Before that, I hid how I felt because I didn’t know anyone else felt the same way. I thought I was weird, a freak. I had severe abandonment and attachment issues and I was ashamed and embarrassed. But I would have given anything to have someone to talk to about how I was feeling. Someone who understood. When I told my support groups members, I was coming here today they asked me to pass on a message to RETHINK Mental Illness. Thank you so much for enabling our support group to exist; for helping to provide a space where they can meet each other without feeling judged. But our group is not a substitute for professional help.

Despite all I have said, I have hope for the future. We have an excellent voluntary sector in this country. We have an army of volunteers willing to help. Peer support is increasing and becoming more valued. And then there’s the next generation; students of health and criminal justice. I have carried out training sessions for some of these groups and they are so willing to learn and to understand. I encourage them to become the kind of professional they want to be, rather than following those who, probably through no fault of their own, have become cynical and jaded.

People with BPD don’t want better care than anyone else. They want parity, and they want to be treated right. No condition should be stigmatised, and no individual should be discriminated against, for any reason. I hope we can all work together to bring about change.

Thank you

Note

Sajid Javid resigned shortly before the event and was replaced by Secretary of State for Care and Mental Health, Gillian Keegan MP.

Unfortunately, the Shadow Minister for Mental Health, Dr Rosena Allin-Khan MP was taken to hospital shortly before the event and was unable to attend.

Speaker of the House of Commons, Sir Lindsay Hoyle, attended the event along with several other MPs.

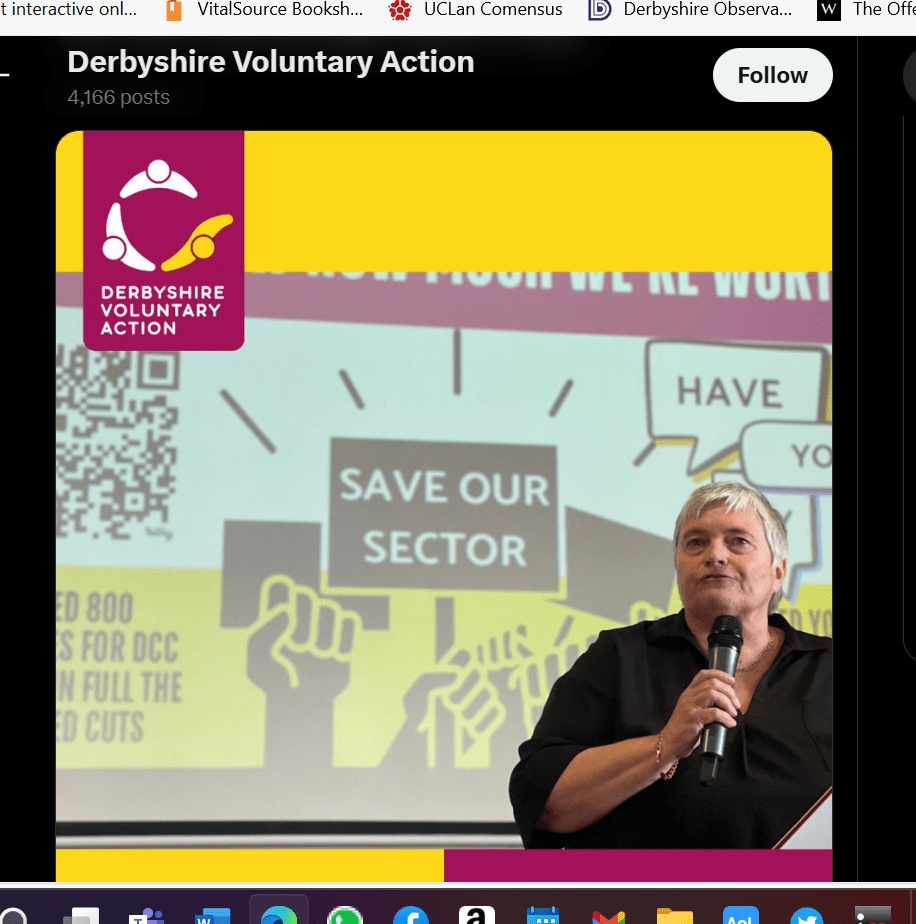

3. Keynote Speech: Derbyshire County Council Consultation

A DVA event, SMH Group Stadium Chesterfield, 17 July 2024

I’ve known about the proposed cuts to the voluntary sector for a while, but when I was asked to speak here today, I thought I’d best delve deeper and get my facts straight. It seems that adult day care centres, lunch clubs, and many of the other vital assets, that people have worked hard to establish and maintain, are in danger of closing. If the proposals go ahead, it will inevitably result in even more suffering for those most in need.

Cuts do have to be made and I don’t envy those whose job it is to make them. But that’s what this consultation is all about, isn’t it? To present to the decision makers at Derbyshire County Council what people think about their proposals, in a respectful way of course.

Like many, I am proud of our voluntary sector and I’m proud to be a part of it. I have several hats, but the most important is the support group I run for those who have borderline personality disorder. There are many groups like mine, who rely on the support and guidance of the larger voluntary sector organisations. Cutting their funding will effectively put an end to many of the smaller groups.

I would like those who are considering these cuts to understand the true value of community and voluntary groups. Not everyone has support in the form of family and friends, and most cannot afford to go private. Until they have adequate services to rely on, these groups can be the only support someone has. But they’re not just social groups that gather for coffee and a chat. For many, it’s the first time they’ve been able to meet others who struggle with the same or similar difficulties.

My support group can’t provide therapy, and our members still need to access services where they can, but I must say, the kind of support they give each other is amazing. They’ve found a sense of belonging, where they’re not judged or ignored. This might not mean a lot to people who are not over-sensitive and paranoid, or don’t often feel the need to self-harm, or don’t act like a child but can’t seem to control it, but our members recognise how difficult it is to manage these emotions and they praise each other for not doing those things. They encourage each other to find distraction techniques and to keep themselves safe.

We provide a website, newsletters, zoom calls and Whatsapp groups, but we also encourage them to develop their own networks between themselves, and many have. They go bowling and meet for picnics or for walks. They want to help themselves and each other; they just need that extra help that a community group like ours can provide.

There are many community groups around Derbyshire doing amazing work. If their funding is taken away, what’s left? My guess is that the long-term consequences on people’s health, and therefore the financial cost on the taxpayer, will far outweigh any money that will be saved by devastating the voluntary sector. Please remember that we who run these community groups don’t get paid for what we do. We’re volunteers, who do it because we’re passionate about helping people. But we can’t do it alone.

Without over-simplifying the issue, isn’t it a matter of priorities? Shouldn’t high salaries come second to ensuring that people have their basic needs met? And by this I am including befriending to prevent loneliness, counselling for the bereaved, day care centres for disabled children and adults, and for older adults. And the many other networks and services that we ourselves may not need right now. But who knows what help we might need in the future!

I don’t usually use the quotes of American politicians, and don’t worry, it’s not Donald Trump, but I think this one is relevant here. You’ve probably heard it before:

“It was once said that the moral test of government is how that government treats those who are in the dawn of life, the children; those who are in the twilight of life, the elderly; and those who are in the shadows of life, the sick, the needy and the handicapped.”[1] (disabled)

What I would like to say to the decision makers at Derbyshire County Council is, please take a step back and think of the consequences of what you’re doing to the people of Derbyshire. By cutting discretionary grant funding to voluntary and community organisations you will, in effect, be reducing the most vulnerable in society to collateral damage. The money you save would be short-term but the problems it could present are long-term and far reaching. Please take note of the views gathered in this consultation. Search your conscience and work together to find a way that does not target those most in need.

Thank You!

[1] At the Hubert Humphrey Building dedication, Nov. 1, 1977, in Washington, D.C., former vice president Humphrey

4. Keynote speech at Comensus Conference (UCLan, 2024)

Speech

Thank you, Mick, and thank you to Comensus, for inviting me here today.

Explain outline of speech (on slide)

Seven years ago, I was sitting in a prison cell, dreaming about what I would do when released. I had a relatively recent diagnosis of borderline personality disorder (BPD) and had quickly learned just how much stigma and misunderstanding surrounds the diagnosis. The judge in my case knew nothing about it and was persuaded by my local community mental health team that it was untreatable and that neither they, nor the probation service, were willing to supervise me. This resulted in me being given a custodial sentence rather than a community or suspended sentence.

I learnt a lot about injustice in prison and how both the mental health and criminal justice systems were failing people, and I wanted to do something about it. I wanted to help people. The thing was, I had no idea how to go about it. Like most people in prison, I knew nothing about experts by experience and how they were working to bring change. As far as we were concerned, no-one cared about us other than our own families and friends.

I have decided to include my prison experience in my speech because health and social care is a vital part of it. Women especially, experience poor physical and mental health and many are living with trauma. I look on this part of my life, and the events leading up to it, as my crisis period. The time since my release I see as my recovery period.

I know there are a lot of people here that are heavily involved in patient and public involvement, and I wouldn’t presume to know more about it than any of you. I want to share my story with you to highlight some of the different opportunities that I found, and also, some of the pitfalls.

So, back to my prison cell . I would start a support group, I thought. Having never attended one myself, I thought they were all run the same, like AA . Hello, my name is Sue and I have borderline personality disorder . Of course, it didn’t turn out like that.

After my release, I was put in contact with someone at Rethink Mental Illness, who helped me to set up the Derbyshire borderline personality disorder support group. It’s now in its seventh year and has helped over 400 people, including several from overseas.

I have always been proud of the group, of course. It provides a space where like-minded people can come together and support each other. But I wanted to do more. I wanted to get involved in bringing change, so that our group will be supplementary to, rather than in place of, adequate treatment.

Through Rethink, I was introduced to Healthwatch, and joined their advisory panel, which was made up of experts by experience. Through my work there, I was put in touch with an agency in London, who were working for prison reform. And through them, I became part of the East Midlands Health & Justice team.

All this happened relatively quickly, but I was enjoying it. I was convinced that I was making a difference, and in some ways, I was. I went into prisons to interview people with cancer on their experiences of treatment. I co-produced and co-delivered a pre-release skills course in a women’s prison and then developed a best practice guide.

I even went back to the prison I was in. I hoped I would see the officers who had, so often, accused me of being an attention-seeker. I wanted to say ‘see, you were wrong about me!’. Unfortunately, or perhaps fortunately , I didn’t see anyone I knew.

I learnt a lot from going into the various prisons. As a prisoner, I could only see one side, which wasn’t always positive. But going in as a researcher, or to deliver a skills course, gave me a different perspective. I saw how overstretched the officers were, as well as the serious lack of communication between each sector of the prison. My colleague and I sat waiting for over an hour for an escort to take us to the interview room because the reception staff were busy and forgot to ask for them.

I thought back to a time I had asked an officer to take me to the visiting room. He said he would send someone to fetch me, but they never turned up and I missed my visit. I took it personally and thought they had done it on purpose. But sitting there waiting for an escort, I could see how easily it could happen.

My biggest achievement at that time, I felt, was being part of the east midlands prison partnership board. It was a partnership between the NHS and the criminal justice system, two organisations I felt passionate about. As a board member, I was able to bring items to the agenda, see them minuted, and then actioned. This was true co-production.

I told the board of my experience in prison after I had fell and dislocated my shoulder. I was left in pain for 5 days before they allowed me to go to hospital to have it corrected.

This kind of lived experience can be particularly useful for those at the top, who are unaware of what goes on a daily basis.

On the board was a prison director, who said that my case must have been an isolated incident. It would never happen in any of his prisons, he said. I suggested, politely, that someone in his position would not necessarily be told of such rudimentary matters.

I knew this director didn’t like someone like me being on the board. Whenever I spoke, he either sighed loudly or looked pointedly at his watch. Fortunately, the Chair of the meetings was the one who had invited me onto the board and made sure I had my say. It was agreed that I, and the rest of the health and justice panel, should carry out research into the subject, and this led to another best practice guide for prisons; this one on escorting prisoners to and from the local general hospital.

At another board meeting, I brought up the issue of physical abuse by officers on prisoners. I told of my own experience of this and was advised by the director to bring an assault charge against the officer. I was surprised at this and thought that maybe I had got the director all wrong. But then he followed it up with, of course that would mean that you wouldn’t be able to carry on with this board because it would be a conflict of interest. I told him that I could do more good by staying on the board, but thanked him for his ‘concern’.

In time, the work I was doing started to affect my mental health. I couldn’t risk another crisis and so decided to take stock of which jobs I enjoyed and which ones I found too stressful. Also, which organisations truly believed in PPI, and which included people with lived experience merely to tick a box to say they did? Was I valued, or was I being used.

Firstly, Healthwatch. Several times they asked me to represent them at multi agency meetings regarding crisis plans, but each time, the police would veto it, saying it was inappropriate because of my criminal record. After a while Healthwatch, understandably perhaps, stopped asking, and so I left.

The agency in London got me involved in several things, which I enjoyed. For example, the cancer in prison project. This had been run jointly by a major cancer charity and a university in the south of England, and it led to me, and the two other lived experience members involved in the project, contributing to a published academic paper.

But then I discovered that the agency had charged the project funders an enormous amount of money just to provide our names. The three of us were paid just £45 per day by the agency and, although I didn’t start this work to make money, I didn’t like the idea that the agency was using me to make money for themselves. So, I left. Around the same time, I left the prison partnership board. I felt that I had gone as far as I could and there were others on the health and justice lived experience panel that could take over.

When I was first asked to get involved in this kind of work, I felt grateful for being asked and vary rarely turned anything down. But I wasn’t always fully prepared. For example, the males I interviewed about their cancer treatment were all sex offenders and were serving long sentences. I went there with the idea that they were human beings, and I had a job to do. But, in subsequent weeks I felt guilty.

I had joked with some of them, mainly as an icebreaker so they would feel comfortable. My colleague and I got the information we needed, but several times we had to stop them from talking about their offences. I ruminated about this for a long time after, the guilt came from the knowledge that I had joked with someone who, if defined by their crimes, were monsters. In a way, I felt like I had let down their victims.

But I learned a lot from that experience. Self-care and self-compassion are vital in this kind of work, whether we interview someone else or share our own stories. If you’re new to PPI, I would advise being selective in what you take on and beware of tokenism & exploitation. Consultation and Informing can be just as valuable as coproduction, but it’s important to recognise what you are contributing. Organisations should not use you to tick the co-production box if that’s not what’s happening. Honesty, trust and transparency are vital. Equally important – you should be enjoying what you do.

As you will know, much of PPI work is voluntary. Payment can be a contentious subject, but I think it’s a matter of personal choice. I was recently asked by my local police to do a training session on personality disorders for some of their 999 call handlers. I was interested, of course, and would have done it for free. But then I was told that, although it’s usual to provide payment for this kind of work, as they do with the carer’s association, the hearing and sight impaired, and the various other organisations they invite, they could not pay me because there was no budget for personality disorders. I felt insulted on behalf of my community. Why were we being treated differently? So, I regrettably declined, but said that I would make myself available as soon as the budget allowed for it.

After giving up so much of my work, I had more time to concentrate on my writing. I was, and still am, an academic. Before prison, I was a historian and wrote a book about disabled children during the second world war. But after my crisis period, my work became all about prison reform and mental health. I had several articles published, including one in Custodial Review, a magazine for the police and prison services.

I decided to write an article for an online journal meant for probation practitioners and researchers. I wrote about the importance of boundaries in the probation officer and client relationship, and it was published in 2021. As an introduction to the article, the editor wrote,

In this issue, we have a challenging article from a service user, Sue W. It does not make for comfortable reading but Sue’s analysis of what could and should have been done differently in her supervision – not only by probation but also by community mental health services – is eloquent, and she argues that achieving the right balance between empathy and professional distance requires a sophisticated level of skill and awareness.

I was proud of the article and pleased with how it had been received by the editor. But a couple of weeks after its publication, a colleague told me they couldn’t find it. The journal was online but without my article. Fortunately, I had downloaded the issue as soon as it had been published so I compared that with what was online now. They were the same in every way, except that my article had been withdrawn. I phoned the editor but was told she didn’t want to speak to me.

To this day, I don’t know why that happened, but it had an enormous effect on me at the time. Fortunately, since leaving prison I have been seeing a private therapist and so was able to discuss it with her. She helped me to move on from it and advised me to stick to the voluntary sector for a while. I wrote a few blogs and participated in health and justice panels, podcasts and webinars. And I became a reviewer for Research Involvement and Engagement, a coproduced journal, which focuses on patient involvement and engagement in all stages of health and social care research.

Then, in July 2022, I delivered a speech at Rethink’s 50th anniversary event held at the Houses of Parliament. The event was attended by Gillian Keegan, who at the time was the Minister for Mental Health and Social Care. She listened to my speech, was polite and encouraging and said that yes, things had to change. She wanted to get involved, she said, but I was sceptical, and rightly so. Two months later she moved into a new post, and we never heard from her again.

I decided to try a different way of raising awareness. Every single day of my time in prison I had written something about prison life. What I saw and how I felt. I talked about other prisoners, the officers, healthcare (which was run by the NHS rather than by the prison) and the prison system itself. How it worked on a daily basis. I had kept everything and now thought it was time to turn it into a book, which I published on Amazon at the beginning of 2023. After that, I wrote about the health and justice system from my perspective, using my case as an example, and I published that at the end of 2023.

Looking back at the work I have done, a lot of it has been by consultation and sharing information, as well as co-production. Here’s a few more examples…

Slides

Conclusion

For those of you who are here today from organisations that already include people with lived experience, or are thinking of doing so, please value them. Their insight is extremely important in making services successful. And please look after them. This kind of work can be enormously helpful to someone who is trying to make sense of their own experiences, but it can also be stressful and exhausting.

Like most people working in PPI, I am passionate about the work I do. It’s helped enormously with my recovery, and I have learnt a lot. And I think I have managed to find the right balance in order to stay psychologically safe. I’ve learnt what my limitations are, the importance of self-compassion and of showing compassion to others, and to try and see both sides of an issue.

But we’re always learning, aren’t we? And I’m looking forward to learning about other people’s experiences and different methods and experiences of PPI at this conference. There are some great speakers lined up, so I hope you all enjoy it as much as I know I will.

Thank you!

5. Service User Speech: HIEM/Mental Health Alliance learning Event, March 2024

Hello everyone,

When I was on a psychiatric unit, I thought people didn’t care. My work with the Collaborative, and events such as this, shows me that people do care and want to work towards reducing the need for restrictive practices

My first time on a psychiatric unit was in the 1970s. I was14 years old and on an adult ward. Several things stand out from that time but the most horrific was seeing an elderly severely mentally ill man in the breakfast room being physically restrained and forcibly fed. It was done in a brutal way and was extremely distressing for the patient, who was left with a bloody nose and mouth. I remember it as if it was yesterday. What I also remember is the lack of any kind of reaction from the other patients. I was transfixed and distressed by what I saw but everyone else looked away and carried on with their own breakfast. I came to realise that this kind of behaviour was accepted.

My next stay on a psychiatric unit was just over 40 years later, in 2015. I didn’t see anything as horrific as that, but I experienced physical restraint myself after having an argument with another patient, and I saw others being restrained. Thankfully, safer handling techniques were used, and no-one was injured. But again, other patients seemed oblivious to what was going on, even though they could hear the commotion, and it seemed to be accepted.

At no time, during both my stays in hospital did anyone ask for the patients’ opinion on anything. Now, 7 years after my last experience, I can see that things are changing. Patients are getting more involved in their own care and trust is being built.

For me, projects like this are important because they show patients and other service users that their opinions do count and can make a difference.

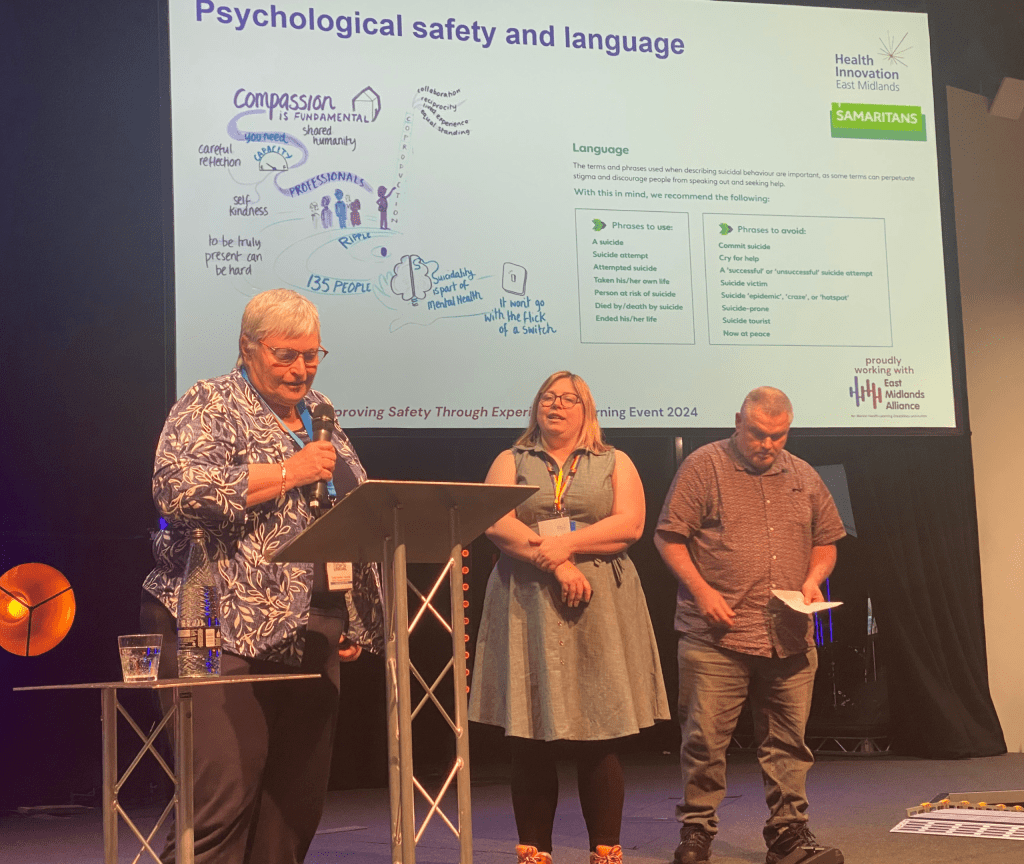

6. Joint Keynote Speech: HIEM/Mental Health Alliance, Nottingham (March 2025)

Hello everyone,

I’ve been involved with the mental health programme, since 2021 and have taken part in all 4 of these learning events. I’m currently in the Preventing Suicide and Self-harm community of practice and have recently been involved in co-producing a video on compassionate phrases. We all know how stigmatising language can be, but it can also be a force for good. By using clear, positive language we can turn a statement of distress from being viewed negatively to a request for help. For example, from attention-seeking to seeking support.

When I first joined the mental health programme, I was part of the reducing restrictive practice workstream. At the first event I spoke about my experiences on a psychiatric ward, back in the 1970’s, when I was a young teenager. I compared it to my experiences a few years ago. A gap of 50 years, which makes me feel very old!

Obviously, a lot has changed in that time, but for me, one of the changes that stand out most, is that I now have a voice and a place to express how I felt as an in-patient. And it’s not just because I’m older. Despite my age, I was put on an adult ward and saw the brutality of force-feeding and restrictive practices. There was an acceptance by the patients, and their families, because they couldn’t do anything about it. They didn’t have a voice. I remember those patients as if it was yesterday. I’m sure none of them could have imagined a time like this. A co-produced learning event where both former patients and staff get together to discuss their experiences of being on a ward, whether as a patient or staff member, so that we can continue to work together and improve safety.

Being part of something like this, where we discuss and listen to issues that are potentially triggering, means that our own well-being should be protected. I know from experience that not all organisations are aware of this, and the mental health of those with lived experience can suffer as a result. This is not the case with the mental health programme. They recognise their duty of care; it’s one of their principles of involvement. From the beginning, I’ve been aware that there’s someone I can talk to if I have a problem, and after every meeting, we’re given the chance to discuss how it’s gone and how we feel. We don’t always take this up; the point is that the help is there if we need it.

Another stand-out moment for me in my work with the mental health programme, has been the webinar I co-produced with staff members Kay and Deborah.

Involving people with lived experience to transform mental health services.

Representing all of us lived experience members, I discussed what we can offer by doing this work, and what we can gain. We can offer commitment as well as our individual insight and skills, such as facilitating, leadership and public speaking, and we can gain new and improved skills.

But the rewards are much more than that. We can benefit from improved mental health (speaking out and helping others can be massive in this respect). A sense of equality (by working together as equal partners). A sense of making a difference and helping to improve services for us and others. And, of course, increased confidence and self-worth.

In other words, involving people with lived experience, if done correctly, can be a win-win situation.

Thank you for listening.

7. Speech at the Mental Health & Wellbeing Faculty Research Theme Showcase, Stafford, 24 September 2025